The Lincoln Memorial: A Centennial Celebration

By Samantha Taxter // Photos by Jimmy ienner, Jr.

April 26, 2022

BERKSHIRE COUNTY residents and visitors will be filled with pride this year as the United States celebrates the centennial anniversary of the Lincoln Memorial. Organizations and individuals nationwide are dedicating countless hours towards recognizing the names and stories of those who made this beloved work of art possible. It is humbling to know that the Lincoln Memorial’s impact on U.S. history can be traced back to the rolling hills and clear skies of the Berkshires in Western Massachusetts.

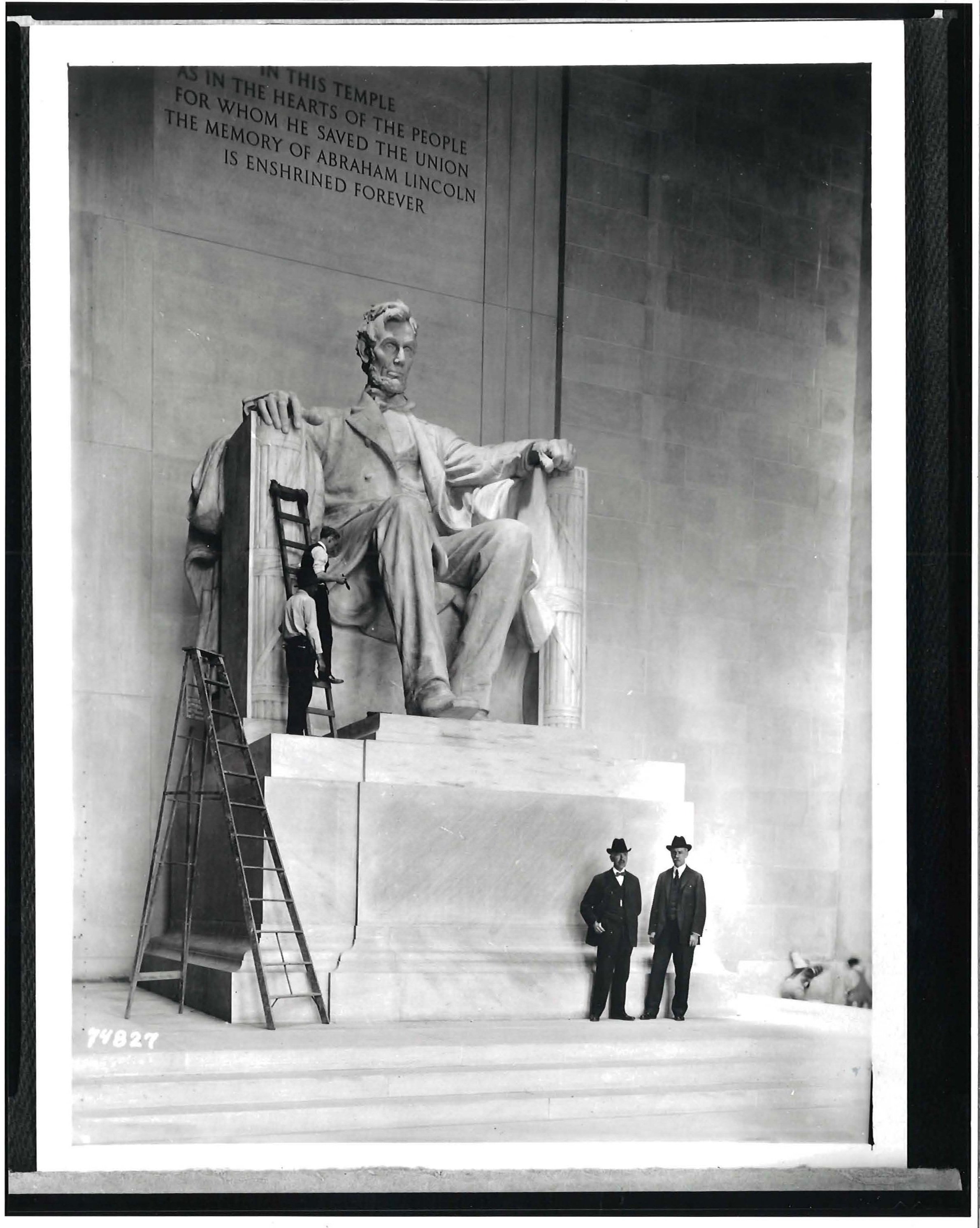

Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The centennial is also an opportunity to appreciate the beauty of where art and history meet. Throughout the month of May and beyond, celebrators can expect events to honor the Lincoln Memorial’s local handprint. Chesterwood, the historic home and studio of sculptor Daniel Chester French in Stockbridge, will open early this season on May 5 to correspond with the May 7 opening of the Lincoln Illustrated exhibition at the Norman Rockwell Museum. (Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer will give a presentation at 2 p.m. that afternoon at the museum.) The documentary film Daniel Chester French: American Sculptor will premiere at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center on May 26, followed by a panel discussion featuring Holzer, filmmaker Eduardo Montes-Bradley, and American art scholar Thayer Tolles. An afternoon of family-friendly events is also planned at Chesterwood on Monday, May 30.

“Chesterwood is where he’s alive. If you want to find answers to French, you have to go to Chesterwood. It’s a little bit like a temple, like a shrine,” says Montes-Bradley during one of his many trips to Stockbridge to research and film. Montes-Bradley hopes that viewers of his documentary will recognize the importance of location and space as catalysts for inspiration and change.

Daniel Chester French’s studio in Stockbridge was designed for creating a number of his public sculptures. French spent 34 summers at Chesterwood, working daily in his studio on such important works as the Abraham Lincoln that forms the centerpiece of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

French was born in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1850. His father, Henry Flagg French, was a lawyer and a judge, later becoming the first president of the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now UMass Amherst). French discovered his love and talent for art after the family moved to Concord, Massachusetts, when he was a teenager. At the time, Concord was where many artistic intellectuals lived, and he was embraced by members of the Transcendentalist community. The French family were neighbors and friends of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Alcott family, and it was May Alcott, sister of novelist Louisa May Alcott, who insisted French become more serious about his knack for sculpture. French taught himself using the small blocks of clay gifted to him by neighbors and friends. He continued his studies with physician and artist William Rimmer in Boston, and sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward in New York, and he received his first commission from the Concord town fathers. French’s Minute Man was unveiled in Concord a day ahead of his 25th birthday, on April 19, 1875, before a crowd that included Emerson, President Ulysses S. Grant, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. French was not present; he was in Florence, Italy, where he worked in the studio of American sculptor Thomas Ball for almost two years. While there, his skills and knowledge of art flourished, and he was given the opportunity to fully indulge in life as an artist.

Plaster casts of hands hang along a wall in Daniel Chester French’s studio at Chesterwood. The hands were cast from his friends, models, family members, and others. Opposite page, French put nails into his copy of the Lincoln life mask for measurement purposes, and it now hangs in his studio.

When his father became assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury in 1876, French set up a studio in Washington, D.C., and also worked in New York. He bought a home in Greenwich Village at 125 West 11th Street in 1888 after marrying his first cousin, Mary Adams French. With the transition from horse and carriage to the automobile, buildings along the alley between Eighth Street and MacDougal Alley that were once stables were up for sale. French bought three buildings with northern exposures and turned them into studios.

He was on the cusp of an emerging arts scene. His neighbors were other well-known artists such as Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who later founded the Whitney Museum of American Art by cobbling together some of those studios. The street was a concentrated area of inspiration and collaboration among great minds. French played an important part in establishing New York City’s arts community, as a founder of the National Sculpture Society, a teacher at the Art Students League, and a trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reflecting on what is known about French’s life in New York City, Montes-Bradley says that the sculptor transcended oceans and brought European art styles to America. He helped to transform Greenwich Village, says Montes-Bradley. “He converted these spaces to allow America to grow artistically. He opened that door.”

Construction of Lincoln Memorial Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, other artists were reaching towards their own dreams in one of America’s most prosperous cities. The six Piccirilli brothers were born to a successful carving family near Carrara in Tuscany, Italy. The brothers and their father relocated to New York City in hopes of discovery within New York City’s thriving arts scene. From their studio in the Bronx, the brothers were a hidden talent behind many major marble monuments erected throughout the city. Due to biases against immigrants, including those of Italian background, the Piccirilli brothers’ work often went without recognition. Sculptures such as Attilio Piccirilli’s The Outcast were reflective of the Italian immigrant experience during the early 20th century. The Piccirilli brothers arrived in America during a time when Italians weren’t welcome with open arms. Finding a sense of belonging was—and still is—a struggle for many immigrants who yearn for the American dream.

Attilio was one of few sculptors at the time who could create pieces that were completely original from thought to product. He and his brothers possessed well-rounded carving skills that were highly sought after. French first connected with the Piccirilli brothers in the 1890s, when one of his projects had been passed into their hands after the original carver backed out of the commitment. The brothers’ good work came as a surprise, and this unexpected partnership continued. After meeting the Piccirillis, French employed the brothers on all but two of his marble commissions. French and the Piccirilli brothers also became great friends, visiting one another for studio parties and pasta dinners.

Lincoln Memorial drawing by Henry Bacon, architect, 1917; Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress.

Over the course of their many shared projects, French and the Piccirilli brothers developed a strong bond through design and carving. Both French and the brothers were immensely skilled; the brothers transformed French’s artistic vision modeled in clay, into a marble masterpiece.

French’s studies of Lincoln—through biographies, photographs, and acquiring a replica of the famous life mask taken by Leonard Volk—provided a framework for his first statue of the standing Abraham Lincoln, created for the Nebraska State Capitol in 1909-12. Volk made the life mask of a beardless Lincoln on March 31, 1860, in Chicago, before Lincoln’s nomination as the Republican presidential candidate. The process involved encasing Lincoln’s face and ears in plaster, allowing the plaster to dry for an hour, and then having Lincoln gradually work the mold off without breaking it. Volk also cast Lincoln’s hands in Springfield, Illinois, immediately after Lincoln’s nomination for the presidency. French obtained replicas of the casts from a supplier. Because the right-hand cast was of Lincoln’s fist grasping a broomstick, French made a cast of his own right hand to portray it resting loosely on the arm of Lincoln’s chair for the sitting Lincoln sculpture.

In 1914, the architect of the Lincoln Memorial, Henry Bacon, chose French to design a statue of Lincoln to be placed at the center of the memorial—by that time, the two had become close friends and had been collaborating for nearly 25 years. French knew that the Piccirillis’ golden reputation among sculptors would be necessary for enacting his vision of the perfect piece. He imagined something grand and welcoming, a memorial that would be immersive for viewers no matter where they stood. The brothers valued his ideas, so it was no surprise that French entrusted them with such an important commission.

Daniel Chester French standing with his model of Lincoln in the Chesterwood studio. Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress.

Much of French’s work followed a similar process. He always started small and worked his way up in size and upgraded material. French would rarely draw his work beforehand. Because he would brainstorm on a chalkboard, historians and archivists struggle to understand the way French planned and how he may have processed his initial ideas. It seems as if his projects almost always began spontaneously. “We have very few preliminary drawings for sculptures that French did,” says Holzer, author of Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French. “It just came out of his fingertips onto the clay.”

Plenty of people wanted a standing figure of Lincoln because they thought it was more dignified, says Holzer, who will be among a handful of speakers at the May 22 Lincoln Memorial Centennial Celebration in Washington, D.C. “French said, brilliantly, that because the design of the memorial was fixed in the building, he wanted something that people can see from the bottom step up to the top as they walk up. If it’s standing, you won’t see the head from the bottom. And he wanted it always to be visible. The second issue was whether it should be bronze or marble. French wanted marble. He really pushed for that.”

Working on the Lincoln Memorial, French started off by drafting a six-inch clay maquette of the seated Lincoln. The model is relatively simple, and it is used as an initial representation of his idea. It is then cast into a three-foot plaster model, which is further enlarged into a six-foot plaster model. This last version is usually used as a reference for the final piece. Both the six-foot plaster model and the final piece could be deconstructed to accommodate transportation, since this work needed to move between French’s studio in Stockbridge and the Piccirilli brothers’ marble carving studio in the Bronx.

The Lincoln Memorial was created during a time in which materials were crated and shipped from New York City to the Stockbridge train station, with the final leg to French’s studio by horse and buggy on dusty country roads. (French would pack up his belongings and work and depart for Chesterwood every May, then return to Greenwich Village in November.) Collaboration with the Piccirilli brothers was time-consuming, and the deadline for a 13-foot marble Lincoln quickly approached.

French was enjoying a well-deserved break overseas in Italy and left the memorial-to-be in the safe hands of the Piccirilli brothers. (French and his family were vacationing in Taormina, Sicily, where his daughter was married in January 1920.) His holiday was cut short when Bacon sent news that the structure surrounding the statue had been finished. French quickly traveled to Washington, D.C., to view the home of what would be his greatest accomplishment. What he saw was beautiful: Bacon had designed the most magnificent building based on the Greek temple of Athena. Made up of marble from quarries across the country, the Parthenonlike structure sat at the top of a gleaming staircase, just as French had imagined. Marveling at his friend’s work, though, gave him the realization that he had misinterpreted the scale of the memorial. He immediately knew that the 13-foot statue wouldn’t measure up to the large structure surrounding it. He had to reevaluate.

French entered a period of self-doubt after accepting his mistake. He feared that he would run out of time and that he’d have to present a memorial that was less than ideal. French and Bacon took photographic enlargements of the statue to the memorial and determined that the figure should be 19 feet in height and the pedestal another 11 feet. French stressed his need for funding in order to reimagine the statue to a larger scale, but his proposal was denied by the Lincoln Memorial Commission. Determined to prove himself, French took matters into his own hands and began modeling the head of what would become a 19-foot seated Lincoln. French arranged to have the head suspended by cables from the ceiling of the memorial at what would be its final height; the head proved to be the focus of the room. It fulfilled its purpose and changed the minds of the commission, earning French the funds to have the photo-enlarged model finished.

Navigating and overcoming setbacks, French and the Piccirilli brothers returned to their carving process. With the same six-foot plaster model as before—that model and the six-inch maquette are on display in the studio at Chesterwood— French laid out the new parameters for a more magnificent Lincoln. An apparatus was used to scale up sculpture by using a method called pointing. A series of little marks on the model were scaled up to correspond with depth and form on the final work in marble done by the Piccirilli brothers. That would allow for accurate replication and enlargement.

French and Bacon at the Lincoln Memorial in 1922. Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress and National Archives.

Twenty-eight separate blocks of white Georgia marble were transported from the Piccirillis’ studio in the Bronx to the memorial building that awaited them in the nation’s capital. Nobody had seen the fully assembled statue, nor did they know if it would even come together properly. Tediously arranging each block in the humidity of Washington, D.C., cast an air of anxiety over everyone on site—French, Bacon, the construction team, even President Woodrow Wilson.

In December 1919 and January 1920, the statue of Lincoln was assembled and completed. The structure was inspected for settling during the construction, repairs were made, and walls and foundations were strengthened when necessary. Now in his 70s, French was up on ladders, troweling and polishing the seams of this giant. He designed the sculpture to be in a room whose doors closed. The incoming light from the side was reflecting off the pool out front and completely changed the shadows as they fell on Lincoln’s face. French went to General Electric and asked them to propose a lighting system, which was never in the plan, and he eventually convinced the government to pay for it.

President Warren G. Harding at the Memorial. Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress and National Archives.

The National Park Service details what went into creating this marvel of a monument. Because the memorial was to be built on drained and filled land, extra care had to be taken with the sub-foundation, which is made up of 122 solid, poured concrete piers with steel reinforcing rods anchored in bedrock. The upper foundation is a second series of piers resting on the primary columns. The top piers are all joined together by poured concrete arches that form the floor of the memorial, later covered with a sheathing of marble. Fill was brought in to build up the circular mound that would be the landscape setting for the memorial. Work slowed considerably when the United States entered World War I because of labor and material shortages. Steel struts were added later beneath the floor to support a larger statue.

Different stones were used to construct the memorial’s chamber. The terrace walls and lower steps comprise granite blocks from Massachusetts; the upper steps, outside facade, and columns contain marble blocks from Colorado; the interior walls and columns are Indiana limestone; the floor is pink Tennessee marble; the ceiling tiles are Alabama marble; and the Lincoln statue comprises 28 pieces of Georgia marble. Once the roof was in place, decorative murals were painted on the tops of the south and north walls, and the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural were carved into the stone beneath the paintings.

Marian Anderson sings to an audience seated in front of the Memorial, at a memorial service for Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes in 1952. Historic photos courtesy Library of Congress and National Archives.

Throughout 1921, roadways and walks were built around the Lincoln Memorial. Trees and shrubberies were planted, lawns seeded, and huge, old boxwoods were transplanted to the memorial grounds. By the time of the dedication on May 30, 1922, what was then called Decoration Day and now known as Memorial Day, all the work was done except for completing the reflecting pool and the interior lighting which were finished within the next few years.

It was a near-miracle that the 19-foot marble Lincoln sat as powerfully as he did that day. “It’s the perfect marriage of architecture and sculpture, in the perfect location,” explains Holzer. French was a mastermind of sculpture and strove to create pieces that engaged the viewer in subtle ways. His work at first may appear too literal or impersonal within its surroundings, yet French used human anatomy and body language to convey his messages. With the expertise of the Piccirilli brothers, the Lincoln Memorial was infused with traditional Italian technique while maintaining the accuracy of both French’s vision and Lincoln’s expression.

The evolution of the plaster maquette of the sitting Lincoln, displayed in the workshop of Daniel Chester French’s Chesterwood studio, a National Trust Historic Site.

Some 50,000 people converged on the National Mall to witness the memorial’s opening, nearly 60 years after Lincoln’s assassination. Despite the sense of achievement that came upon Decoration Day, there were many issues that surrounded this momentous occasion. Racial segregation at the event contradicted its purpose. Black Americans who attended were segregated from the rest of the crowd on hand. The area where they sat was not just designated but it was roped off. Dr. Robert Moton, one of the most important Black leaders of his time and the second president of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, was asked to deliver the keynote address. Twelve days prior to the dedication, Chief Justice William Howard Taft, president of the Lincoln Memorial Commission, asked to review Moton’s speech. Finding it to be too radical, he insisted that several sections be removed, particularly those that criticized the federal government for its failure to protect the rights of African Americans. Moton, who was barred from sitting on the platform with his fellow orators, reluctantly agreed to remove his controversial rhetoric.

It wasn’t until Easter Sunday 1939 that the image of the memorial changed, when contralto Marian Anderson sang “America (My Country ’Tis of Thee)” at its steps to a fully integrated crowd of 75,000 people. She had been refused a performance at Washington’s Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution because she was Black. Over the years, the Lincoln Memorial has become America’s backdrop. On August 28, 1963, its grounds were the site of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where an estimated 250,000 people came to the event to hear Martin Luther King, Jr. deliver his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. At the memorial on May 9, 1970, President Richard Nixon had a middle-of-the-night impromptu meeting with protesters who, just days after the Kent State shootings, were preparing to march against the Vietnam War. It is the most-visited national monument, inspiring those who wish to look up the gleaming marble staircase and meet Lincoln’s honest gaze. Filmmaker Montes-Bradley believes that “the Lincoln Memorial is the only place that keeps and preserves the memory, the thoughts, the legacy of Abraham Lincoln.”

Today, the memorial looks forward to restoration after 100 years of weather, tourism, and celebration. The National Parks Service has revealed plans for cleaning, renovation, and repairs. Visitors can expect a more accessible undercroft, complete with a bookstore and restrooms, as well as art exhibits and other informational areas.

Here in the Berkshires, French’s efforts and Lincoln’s mission are highlighted. French spent every summer at Chesterwood for 35 years, receiving sculptors and other artists as guests. French had an immense love for the Berkshires, which reminded him of his roots in the country and served as an outlet for creativity. He referred to the Berkshires as his “heaven,” a place that offered him solace and escape from the pressing demands and speed of the city. The centennial celebration of the Lincoln Memorial shines a light upon the significance of the small town of Stockbridge. Residents and appreciators of Berkshire County are encouraged to use this time to reexamine their roots and the importance of home, as French did throughout his own creative process.